Regional British Crafts: SHEFFIELD

The Steel City

Set in the rolling hills of South Yorkshire, the city of Sheffield has seen the evolution of industry and changes to crafts over the years right on their doorstep. Most famous for their metalworks, specifically steel, Sheffield also once was the number one place to get cutlery in Britain. With raw materials such as coal, iron ore, millstone grit (used for grindstones) and ganister being plentiful in the hills surrounding the city.

The word cutlery literally means ‘that which cuts’ and the first reference to cutlery in the Sheffield area was in 1297 with tax records of a man named Robertus Le Coteler (Robert the Cutler). In fact, one of the items recorded to have been in the possession of King Edward the III was a Sheffield Knife.

Noted in the 14th century for its production of knives and later overseen by the Hallamshire Company of Cutlers, Sheffield became the second largest cutlery manufacturer in Britain after London. However, as iron began to be supplanted by steel, much of the steel had to be imported from Sweden as a method of creating good quality steel hadn’t been discovered in Britain yet, however, the discovery of ‘Blister steel’ changed all this. By heating iron and charcoal together in a specialised furnace, known as a cementation furnace, for 7 days or so, the metal would carbonise and become a rudimentary form of steel. This steel was then hammered into bars, helping to evenly distribute the carbon throughout the steel, improving strength. This form of steel would allow for many ore uses and more reliable products to be crafted that would last longer.

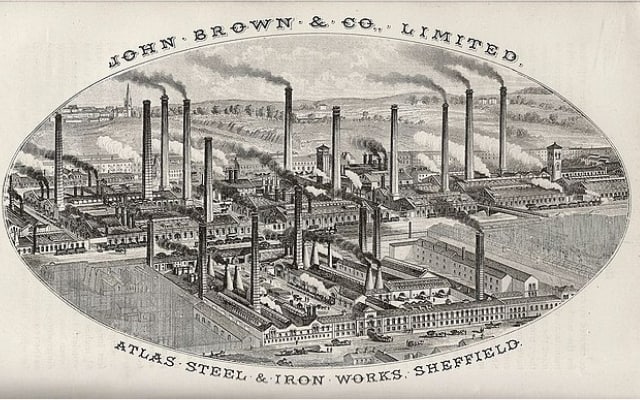

By the 1700s Sheffield had firmly established itself as the place for metalworks in Britain and had a notable glut of metalworking establishments. In 1727 Daniel Defoe wrote a series of books titled “A Tour Tho’ The Whole Island of Great Britain”. In these books he described Sheffield as; “Very populous and large, the streets narrow and the houses dark and black, occasioned by the continued smoke of the forges, which are always at work: Here they make all sorts of cutlery-ware, but especially that of edged-tools, knives, razors, axes and nails. And here the only mill of the sort, which was in use in England for some time was set up, for turning their grindstones, though now ‘tis grown more common.”

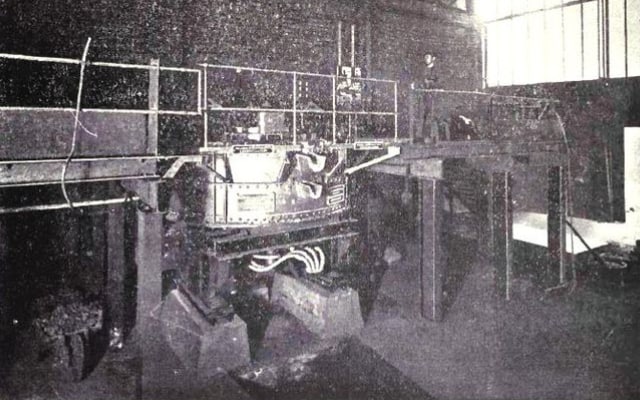

Fast forward a few years and a clockmaker named Benjamin Huntsman (a name that gets the SGB seal of approval) who lived in Handsworth, invented a form of crucible steel production that surpassed the methods of the time. By heating his furnace with coke (coal that has been heated in a partial or full vacuum) he was able to achieve a temperature of 1,600 degrees celsius. He placed clay pots known as crucibles into the furnace and removed them when they were white hot. Blister steel was placed into the crucibles and a flux (a chemical cleaning agent) to remove the impurities. After several hours, the crucibles were removed, molten slag was skimmed off and the liquid metal was poured into moulds. This form of steel had a much higher tensile strength and hardness compared to other steels at the time.

The 1740s saw yet more innovation with metalworks with the invention of a more advanced form of Silver Plating. Thomas Boulsover used a process of fusing a thin sheet of Silver onto a copper ingot to achieve the result that became known as a Sheffield Plate. The Old Sheffield Plate was hand-rolled and primarily used for creating silver buttons for clothing. The old process was time consuming however and was easily supplanted by Boulsover’s method. This new Sheffield Plate method was used in 1751 to create silverware by Joseph Hancock who, due to the prosperity and success of the methods, built the water-powered Old Park Silver Mill. As the use and development of technology began to grow the Boulsover method was rendered obsolete by simpler and cheaper electroplating in the 1840s.

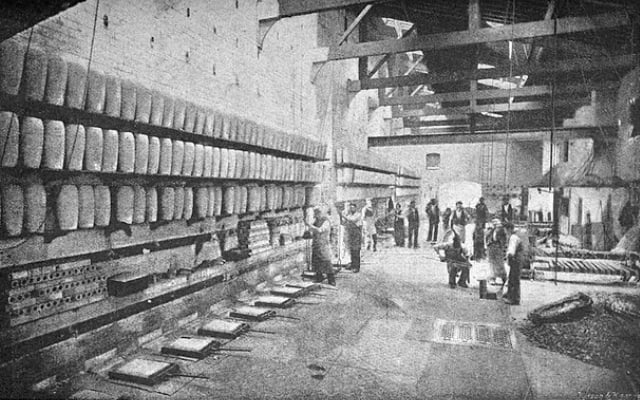

As steam powered machinery began to grow in abundance through the 1780s traditional manufacturing methods began to fade, but not in Sheffield. Some Factors (factory owners) wanted to bring the entire process of manufacture under one roof to ease production and creating the first factories at the same time. But the majority of metalwork was still done by persons known as ‘Little Mesters’. Little Mesters were highly skilled craftsmen, working in small workshops often in their own home, where they worked with a small team of labourers, comprised of apprentices and regular employed individuals.

Each Mester would have one part of the manufacturing process that they specialised in, be that forging, grinding or hafting (creating the handles). This meant that a single piece of cutlery would pass through the hands of many-a Mester before the piece was finished and would keep traditional methods alive. The Little Mesters would further specialise by either focusing on a single type of cutlery or by only working with a single metal type. Unfortunately Little Mesters and their methods went into decline in the 1950s onwards but there are still a few Little Mesters in Sheffield today, a true testament to the crafts and craftsmen ways standing the tests of time.

The 18th century brought industrial mass production of steel to Sheffield and with it a change to the city itself. Many of the town's mediaeval buildings and infrastructure was replaced, gradually, with Victorian and Georgian buildings. The fast flowing rivers of the landscape allowed industry to flourish in Sheffield as it was an ideal place for water powered industry to be situated. The growth of Sheffield through industry also gave rise to several new discoveries, one of which was Britannia Metal, a pewter alloy that resembled silver.

Benjamin Huntsman’s process became obsolete in 1856 with the invention of the Bessemer Converter by Henry Bessemer (funny he called it what he did eh?) but crucible steel maintained its usage up into the 20th century but for much more special uses such as rails for trains as Bessemer’s methods didn’t produce steel of the same strength.

Bessemer tried to get steelmakers to adopt his methods for production but they were unmoved. To get around this issue, Bessemer built his own steelworks in Sheffield and began to produce his own steel. He grew his production until there was serious competition between the already established manufactures of steel and Bessemer himself, but the older companies also noticed that Henry was underselling them by up to £20 (£1750 today) per ton of steel, no small amount. Stainless steel was discovered in 1912 in the Brown Firth Laboratories in Sheffield by Harry Brearley. Brearley was succeeded by Dr William Hatfield who continued to refine the process until 1924 when he patented “18-8 stainless steel”, an alloy that is still the most commonly used alloy of its type today.

As you can see, Sheffield definitely earned the name The Steel City, the innovations from this town has changed the world and helped usher in the industrial age. Metalworks were the lifeblood of the city in years past and have made their mark on both the city and the landscape, but while some see these as scars, they should be seen as signs of a truly remarkable area with a history as strong and as important as the steel they produced. Others have made a much more positive impression on the city as a whole, such as the football team of the city, Sheffield United, being nicknamed “The Blades”. A callback to the past industry of Sheffield and a proud reminder of the heritage they honour. The Legacy of Sheffield, even after the production of metals is no longer the lifeblood of the city, is stronger than the steel they produced.