Coniston Stonecraft INTERVIEW

The story behind a product hundreds of millions of years in the making

We're welcoming you back to another craftsmanship interview. This week, we sat down with Brendan Donnelly the owner of Coniston Stonecraft, and George one of the highly skilled stonemasons in the team to find out more about the age old business of slate craftsmanship. They give us insight into the history of slate production, why Cumbrian slate is a far superior product, a bit of Cumbrian slate lingo, why Coniston Stonecraft are an eco-conscious outfit, and the pleasures and challenges of working with one of the most beautiful but difficult materials in the world.

SGB: Let’s start at the very beginning Brendan, give us a brief history of Coniston Stonecraft.

Brendan: Making things from slate has been done on our mountain for hundreds of years, we have more quarries and mines on the Old Man (our mountain in Coniston) than you can shake a stick at and for many years slate working was the main employer of local people. Coniston Stonecraft's story begins when the Coniston to Barrow railway was ceased in 1965, the copper sorting sheds were no longer needed and slate utensil production began using slate straight from the local quarries.

SGB:Have you always been involved in the slate industry?

Brendan: No, I came to it late but once bitten it becomes all consuming

SGB: Were there any struggles along the way to become Coniston Stonecraft?

Brendan: I could write a book. Taking on a business that is in receivership, in an industry in seemingly terminal decline is not for the faint hearted. Storms, floods that bring down bridges, power outages. Life is one long struggle here.

SGB: What is it about Cumbrian slate that you love so much?

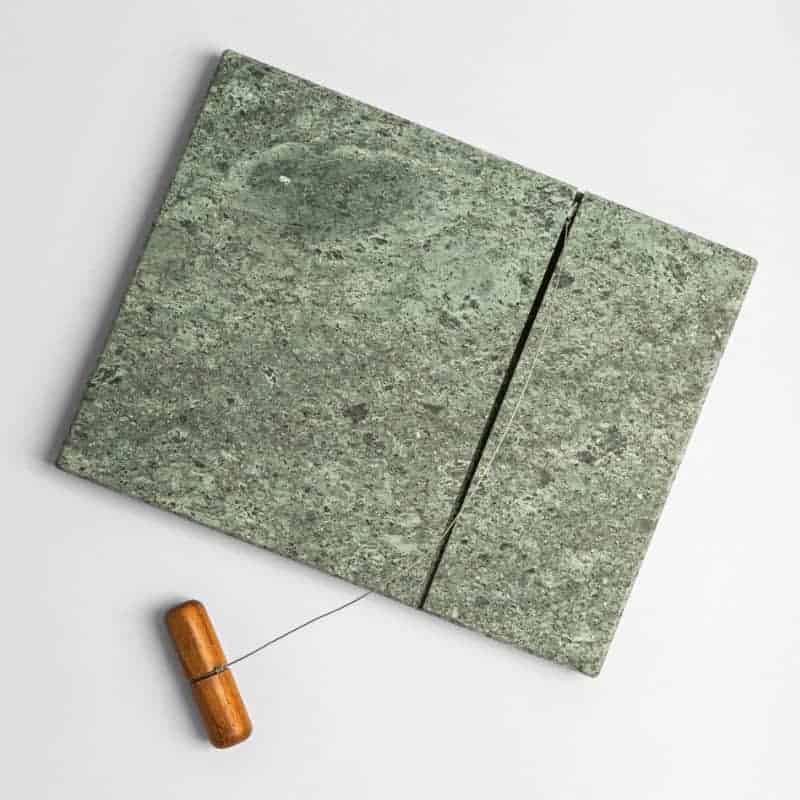

Brendan: It is unlike any slate you can get anywhere else in the world, the variety of colours the mix of pyrites and spar and copper and iron just mean that our raw material cries out to be made into something beautiful. And of course here in Coniston we are at the epicentre of that variety because we have 3 bands of slate surfacing on the mountain: Westmorland green, Brathay blue grey, and Coniston silver grey.

SGB: Why does Cumbrian slate differ from other British slate and overseas imports?

Brendan: The beauty and variety of colours makes Lake District slate so unique. You can get green slate from China, but is a dull mono shade of green. You can get a nice black slate from Brazil, but it is blacker than Brathay and doesn’t have any of the intricate features of our local slate - no runs of pyrites or mud lines or mineral traces. Their slate is like a night sky with no stars, whilst ours is like watching the Milky Way when there is a comet shower.

SGB: So with that in mind, tell us more about the quarries in Cumbria. Which quarries do you make your beautiful products from?

Brendan: We draw clog (untreated hewn stone) from several quarries all in the local area, and I entrust George and Andy to guide me on the suitability of the stone for what we want to do with it. So our nearest quarry is owned by the National Trust and worked by Mark - Guards Wood, just at the top of the Lake about 2 miles away. It produces lovely blue grey slate with lots of mud lines for added interest. We also pull from the peat field quarry which is worked by Billy and Isaak, and is part of the old Hodge Close complex. We get some really interesting Westmorland green slate from there and it’s only about 4 miles away. Other quarries we pull from are Elterwater, Kirby, Broughton, High Fell. And for our limestone we go all the way to Ulverston (12 miles) and get the beautiful creamy Baycliff limestone which is a sedimentary rock full of long dead sea creatures.

SGB: How does slate differ from quarry to quarry?

Brendan: Chalk and cheese. High Fell is a tight grained green slate that is incredibly hard and difficult to work. Elterwater is a beautiful light green and softer to work. It’s not even the difference from quarry to quarry, there is a huge difference often from clog to clog from the same quarry. We try to be consistent but we can never make two objects the same.

SGB: What is your personal favourite quarry and why?

Brendan: That’s like asking which is your favourite child, I like them all but depending on what we are doing it can be a movable feast as to which one is my favourite.

SGB: With such a huge variation in the slate, can you tell us more about the challenges of working with a naturally variable product? In a world where monoform, identikit, mass manufacturing is so prevalent and the norm for consumers it must be a curse and a blessing?

Brendan: Our quality control is a vague thing. I could show you slate from each end of a piece of clog and you would swear they were from different quarries. It’s not unusual to have runs of pyrites-fools gold running through the piece and a run of this, what we call 'spar', can look magical or a bit like a crack. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder and we frequently get pieces returned because of their look. But those pieces are snapped up almost immediately by our visiting customers because they are so unique. Our aim is to make beautiful pieces, not to tell customers what to like or not like.

SGB: Another great thing about your business, and Cumbria in general, is the language. Tell us some slate lingo and their meanings.

Brendan: Clog is the boulders that you get from the quarry. Rive is the process of splitting two faces of rock apart Bate is the natural lines of weakness that allows the trained slatemason (George) to rive open a piece of clog using only a hammer and chisel. Mud marks or mud lines are quarryman’s terms for lighter streaks in the slate, they have nothing to do with mud or sedimentation (slate is an extruded rock unlike limestone).

GB: At SGB, we like to promote conscious consumerism. Tell us about your eco credentials.

Brendan: We try our absolute best to be an ethical and ecologically sound company. We get all our stone locally (although it’s cheaper to use imported stone). We use electricity from the hydroelectric station about 75 yards away which turns the fast flowing Church Beck into electricity. We cool all our machines not with oil but with water from Mines Beck (incidentally this gives our slate a beautiful clean tactile feel that so many of our customers love). We use only recycled material in the packing process, so our cardboard is bike boxes from local bike shops that would otherwise go to landfill, our cloth is from a local fabric company that lets us have their seconds again they would otherwise send them to landfill. And we have a tie in with a very worthwhile charity in Kendal that train people to reupholster sofas, we give them excess cloth, and they give us foam for cushioning the slate we send out. We are a yearly audited green small business and we are constantly trying to become even greener.

GB: Why is sustainability important to Coniston Stonecraft?

Brendan: Its important for everyone we just have the opportunity to walk the walk so we choose to do that. If people want to buy cheaper slate and don’t care about where it’s from and what that means for the carbon footprint, it’s not our job to criticise that choice! But if you want to choose the green option then we are one of those choices.

GB: What impact do you think being British made has on your products and your brand as a whole?

Brendan: I honestly don’t know. We live a simple life here on the mountain and we concern ourselves with making beautiful objects and products, doing the right thing and just hope that this is important to our customers. It seems to work because we’ve never been busier. Being true to our roots culture and community is a major motivation for us, if it is a reason for people to buy our products then that’s helps everyone.

GB: Is there anything exciting in the pipeline for Coniston Stonecraft?

Brendan: We are progressing some interesting collaborations with seriously talented people which we hope will result in some beautiful pieces for new markets, ie we tied in with a local glass artist to produce some beautiful slate-glass objects both for in home and outdoors and people certainly seem to like them.

SGB: George, tell us about your slate masonry journey; why did you choose to work with slate?

George: I was offered the chance to change careers about 16 year ago and I’ve never looked back.

SGB: How did you become involved with Coniston Stonecraft?

George: I left farming and had a months trial 16 year gone I guess I must’ve passed.

SGB: Is it true that you can see into a piece of slate before anyone else and understand what is best to make from it?

George: I have a good understanding of the clog but you only ever see inside when you open it up, but I can spot a bath line easily which is a rare skill.

SGB: What are the challenges for you when crafting goods from the slate?

George: Fissures, weaknesses in slate that you only see when you are working on a piece, sometimes you are almost finished and a crack will ruin all your work.

SGB: What is your favourite tool in your workshop?

George: I like the giant polisher it’s very old but flattens the slate well and produces a lovely finish to the slate. The drawback is, because it’s beck cooled, if you don’t wear the waterproof gear you end up soaked..

SGB: What is your favourite product to make from slate and why?

George: I like making rolling pins, they start off as raw clog and when they are finished you really see the beauty of the stone, apparently they are great for pastry but I think they should be ornaments as sometimes they are so beautiful.

SGB: What is the hardest thing about crafting goods from slate (Ed. apart from the slate, quaff quaff)?

George: The process, it’s not like turning on a machine - each piece takes about 20 different operations from riving to sawing to polishing to linishing to carving, infilling glueing waxing etc etc it often takes days. It’s not a quick process and every operation brings its own risks.