British FURNITURE

A Brief History of Furniture & Britain

British Furniture, it is a big subject

This edition of Gordon’sBUGLE Sir Gordon has decided to delve into the world of British furniture, both design wise and manufacture of. There is a part of Sir Gordon that thought this may be a blog too far. The depth and breadth of the subject is vast. And each era and each piece of furniture probably requires a book on its own (in fact we are sure it does). But fearless, Sir Gordon is about to take a leap and journey around British furniture.

The problem is where do we start and what to focus on? From the very earliest days of carving tree stumps or rocks into seats? Or from the middle ages where furniture began to be more common with the advent of joinery?

Well, we have decided to start at the beginning and move through the styles in chronological date order to keep it as simple as possible. As much for the writer as for the reader. Please forgive us if we have not got everything in order and if we skip part of British furniture history if it was slightly blurry to us. And as with any design history, styles blend over time so some dates may be in dispute. We have also not included many certain styles that began in other countries even if it was taken up by British furniture manufacturers.

So, take a seat.

Britain it is believed has some of the oldest furniture still in existence. Skara Brae. A Neolithic settlement of 8 stone houses on the isle of Orkney has examples of stone furniture. Including a stone dresser, which face the main door to display carved art and other artefacts to show their wealth and standing. The settlement dates back to 3100BC which is in fact older than Stonehenge.

The Beginnings of Furniture

During the early middle ages or dark ages in Britain there is little evidence of furniture and furniture design. That of course doesn’t mean there wasn’t any. They were very rudimentary objects, probably unchanged much in design from antiquity. Large stones used as tables, tree stumps carved into chairs and beds made of moss. And those that were made of wood have not survived. Probably because wood doesn’t last that long and very little furniture was actually produced. There is also little evidence in literature or art. The epic 7th century Anglo-Saxon poem Beowolf, the go to source of Britain culture of the time, mentions only benches and a throne but no other furniture.

Edward the Conqueror is seen in the 11th century Bayeux tapestry. There he is sitting on a seat similar to a Roman sella curulis, a throne-like seat with two horns or carved legs crossed either side of a seat made of leather or fabric. This is of course unlike Egypt or Greece where the preservation of organic material due to its arid climate has left much evidence of furniture from those periods.

The Middle Ages are when furniture became, well, what we would call furniture now. Britain had a wonderful and abundant source, native oak. Oak is a wondrous material, strong, durable and with a golden hue. The rise of dedicated craftsmen also aided the use of oak, as it is such a dense hardwood it needed the skills of trained turners and carpenters. The most important piece of furniture in Britain at the time was the chest, coffer or trunk. It was originally known as a trunk because it was simply a hollowed-out tree trunk banded with iron. The most popular piece of furniture was known as a hutch, which was a leap in joinery skills. Instead of 6 planks attached to each other, the sides of the Hutch also integrated legs. A trunk that was used in many ways when one wasn’t travelling. It also doubled up to become a bed, a chair, a table and a desk.

The Medieval times were crude and stark in more ways than one and the furniture of the time in Britain mirrored that. Big, bold and dark. With brash ornate carvings at the head of each object. But these objects were few and far between in houses, even those of the wealthy. It would be common for all but the Lord to be seated on a bench or a stool, whilst the Lord sat on a large chair. And even in most castles there would be only two beds, one for the Lord and one for important guests. Everyone else would sleep on the benches or on the floor in the hall. When it comes to furniture this is often known as the Gothic period taken from the French and Italian styles. But as with any style these Gothic pieces morphed over time to become more British as we move into Elizabethan times.

Famous British Pieces of Furniture

During the 1600s one of the most famous of all British items of furniture appeared. Originally fairly plain, the Welsh dresser was made of solid oak, utilitarian and sturdy. But during later periods of British furniture design Welsh dressers also came in Gothic Revival and Art and Crafts styles. But the Welsh dresser wasn’t just a mainstay from Wales. There was the Scottish dresser too. The uniqueness of the Scottish Highland dresser was that it had a tin lined porridge draw. This draw had hot porridge poured in and allowed to set, then would be cut into slices when cold and handed out to crofters to be taken out into the fields to work.

The Elizabethan period (1558–1603) is known as the Golden period of British history. And the furniture begins to take a distinct character of its own. Although its main cues are still Gothic it becomes more ornate. Turnery became a highly skilled profession and Elizabethan furniture became far more elaborate, with intricate carvings and inlays. Oak is still the dominant wood due to its abundance but other more exotic woods were being used to show wealth. Walnut for the main structure but ebony, pear, rosewood and ash were being used for the inlays. Although the artistry was high it was still not as over the top as many French or Italian pieces of the same period. The iconic British furniture of the time was the four-poster bed. Resplendent with heraldic reliefs and battle scenes all carved by master carvers.

International Influence on British Furniture

The Jacobean period then runs through the 1600s and sometimes known as the Stuart period, the Commonwealth period, even the Restoration Period. And in 1690 the walnut age began. Although similar as you would expect from the Elizabethan period of furniture the pieces began to be influenced by the Dutch and Flemish. With lines becoming straighter, with straight backs on chairs with ball feet and chests of drawers becoming de rigueur.

Cane started to become popular during the 1660s in Britain as the trade with the East Indies was thriving. Cane or Ratan seats and backs of chairs not only looked good and modern but were more hygienic. This was due to the fact that upholstered furniture was a trap for bugs and mites. As the wool that was used to stuff the chairs was a breeding ground.

A distinct technique originated by English cabinet makers around the 1660s was Oystering or Oyster veneer. Which was a short-lived style but does look rather splendid. Oystering is a form of parqueting. The technique uses very thin slices of branches from walnut, crocus and kingswood in cross sections. The slices are then laid side by side to create decorative patterns. The rings of the wood resemble oysters and so the name of the veneering was born.

With the Dutch influence becoming more influential in Britain it was only right that the next style change in British furniture was the William & Mary style, not to snappy a title but it did have a pronounced influence. After James 2nd of England was deposed by his daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange in the Glorious Revolution they settled in Britain. With that they bought their tastes, as well as their favourite furniture makers. Such as Daniel Maret and Gerrit Jensson, who began to supply the wealthy members of British society.

The Queen Anne style or late Baroque as it is sometimes known runs from around 1720’s until the 1760’s although oddly as it is named after her, Queen Anne reigned from 1702-1714. The style is less ornate than its predecessors, whose structure would be sturdy and straight with exquisite inlays and veneering. Queen Anne furniture on the other hand is smaller and delicate Their structure is more curved, utilising S scroll, C scroll and ogee (S curve) with far less decorative elements, such as inlay, paint or veneering. Cabriole leg is the "most recognisable element" of Queen Anne furniture. We first begin to see the winged armchair in this period

Chippendale & Neoclassicism

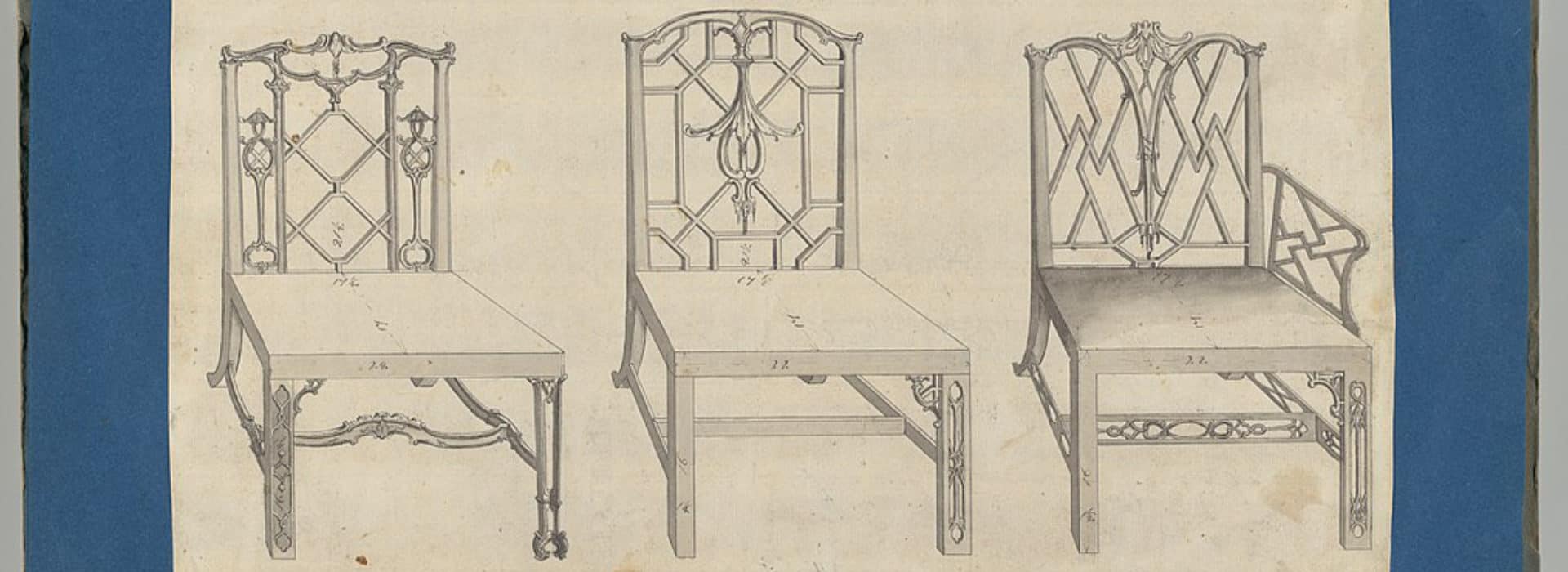

Then came the titan of British furniture making. Yorkshire born, John Chippendale (1690–1768). Probably the first superstar cabinet maker who had a global reputation. Known as the Shakespeare of furniture making. Although it wasn’t so much his actual furniture which set his fame globally, but his book. 'The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker's Director'. A book of all of his furniture designs. From Gothic, Chinese and Rococo (Modern French) and finally in the third edition Neoclassicism.

With the book published, furniture makers around the world copied his designs. From Denmark to Portugal and the US you will find ‘Chippendale’ furniture by local craftsmen. Chippendale was also an interior designer. Designing some of the country’s best private homes and in turn becoming an influential taste maker. Late Queen Anne and early Chippendale are often mistaken with each other (so we gather).

The next big thing in furniture design was Neoclassicism that rose through the Georgian period. A period of 100 years of peace from 1714 to 1830. If there is any era that defines Britain’s place in the world of furniture design it is the classical Georgian Era. Britain’s global reach, financial might and power was growing. With this it had a remarkable blossoming of literary, artistic and architectural scenes. From Charles Dickens to Indigo Jones and the Adam Brothers, particularly Robert Adam. When it came to furniture design and making two things happened. First, the love of classic Greek and Roman architecture. Palladian or Georgian Palladian was a love of columns and pediments of classic antiquity. And secondly, the shortage of walnut due to disease that ravaged the walnut population, in its place was the mahogany imported from the West Indies colonies.

Apart from Chippendale three other great British furniture designers took the world by storm; William Kent, Thomas Sheraton, George Hepplewhite who all worked from the influence of Andrea Palladio whence the name Palladianism comes. This was a period of masterful craftsmanship when style and function worked in perfect harmony. Maybe that is why the invention of the most British of furniture appeared around that time; the Chesterfield. The story goes that Lord Phillip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield required a low sofa, with buttons that allowed gentlemen to sit upright without creasing their suits. The Chesterfield is still seen around the world and is an iconic piece of furniture. And Timeless Chesterfields still manufacture them utilising traditional craftsmanship skills.

Victorian Furniture

The same cannot be said of the Victorian era (1830-1890) which brought about a hodge-podge of design and a severe lack of craftsmanship. Probably due to the empire influencing many aspects of life in Britain, Queen Victoria being a known lover of the ornate and the industrialisation of Britain meaning the first ‘mass manufacture’ of furniture for the newly created middle class. Victorian furniture is often hard to distinguish because of these influences. Gothic, Elizabethan, Rococo, Neoclassical and colonial Asian merge to create a wonderfully eclectic era but hard to define.

It is thought that the Gothic revival probably became the most popular in upper circles but the over the top Rococo style that sat in most of the newly formed middle-class abodes. But the furniture of the time, particularly the rococo style was quickly and cheaply made in factories. With elaborate veneers, ornaments and papier mache placed to conceal the lack of craftsmanship in the furniture. All trousers, no knickers as Sir Gordon’s Grandmother would say. The Times even said when seeing Victorian furniture at the 1851 Great Exhibition ‘It seems to us that the art manufacturers of the whole of Europe are thoroughly demoralised’

Arts & Crafts Movement

The greatest thing to come out of the carbuncle of the Victorian era was the Arts and Crafts movement. The very British backlash against the growing industrialisation and commercialisation of Victorian Britain. Its principle calling was ‘Truth to Materials’ with a visualisation in ‘Simple Forms’. No more hiding bad craftsmanship with Papier Mache or ornate ‘add-ons’ but exposure of the craftsmanship, leaving the skills of the craftsmen and women in the joints exposed. Most was made from oak and had influenced by the nature of Britain.

The most famous proponent of the Arts and Crafts movement was of course William Morris. Who in his 1879 book The Art of the People said “…art made by the people, and for the people, as a happiness to the maker and the user.” Which is something that Sir Gordon Bennett certainly subscribes too. There are two ironies about the Arts and Crafts movement; firstly, it was expensive and the ‘people’ that William Morris so believed in couldn’t afford them. And secondly Arts and Crafts movement furniture, with its straight lines, square legs and simple design, that went against the ornate Victorian styles were simple to copy and easy to mass manufacture, much to the annoyance of founders of the movement.

In the 1880s a new group of architects, designers, interior designers and furniture makers appeared. And with them a new strand of the Arts and Crafts movement. The Scottish School or Glasgow Style had a new take on utility and design. This was furniture designed for modern living. Its ethos was above all craftsmanship and instead of finding inspiration in the countryside of England they used Celtic and Scottish baronial symbols to add simple decoration. The most famous proponent was Charles Rennie Macintosh claimed the style showed restraint and economy over elaboration and artifice and light and shadow over pattern and ornament. Mackintosh’s furniture is heavily influenced by Japanese simplicity in style and a new phrase was termed Japanisme. Some believe that Macintosh was a pre-curser of Art Deco.

Furniture Globalisation

Like the Victorian period the Edwardian period from the early 1900’s was another mash up of styles. Houses were becoming smaller and thus the furniture makers of the period started making furniture smaller. Taking influence from pretty much anywhere they fancied; Tudor, Baroque, Rococo Aestheticism, Art Nouveau and blended into a non-descript yet unique style.

During the 20th Century as the world grew smaller through ‘cheaper’ travel, the advent of picture houses and television appearing in the corner of British front rooms, unique British styles pretty much diminished. Furniture styles came from more than one source with British design helping to guide these styles but not in originating them.

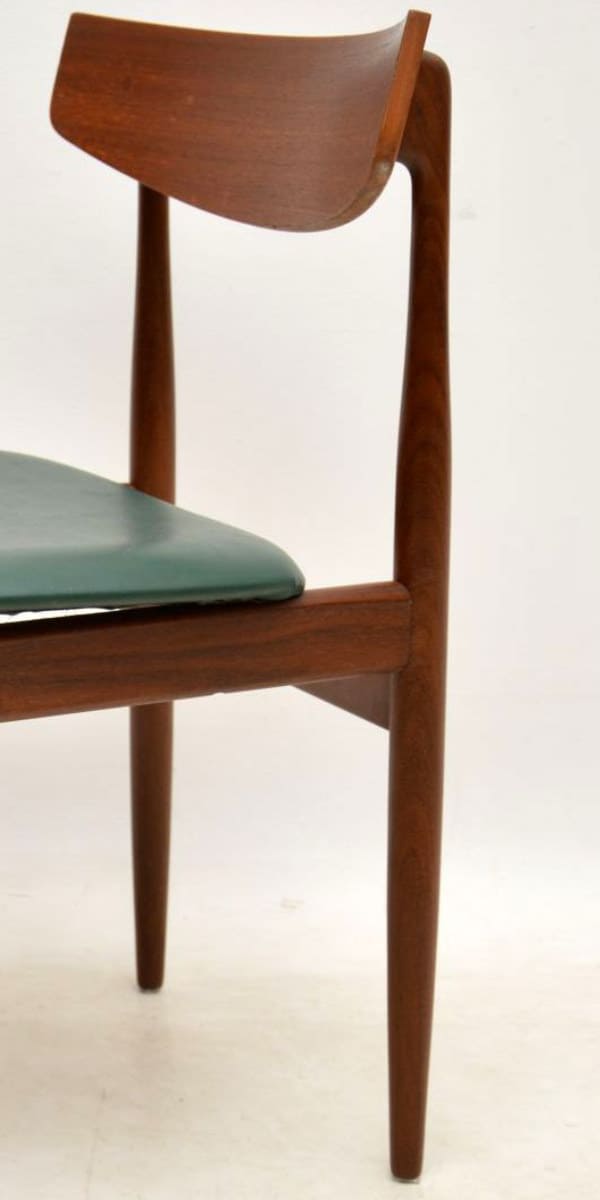

During the 1920s Art Deco came to these shores and although Britain took to it like most countries, it was France and the USA that created and mastered the style. Whilst Bauhaus, Le Corbusier and Eames were instigators of mid-century modern (a term only coined in 1984). Although British manufacturers such as G-Plan, which was founded in 1898, did produce a range of modern furniture to suit all budgets for furniture hungry customers after furniture rations were lifted in 1952 it then introduced the Danish Modern Range in the 1960s to compete with Scandinavian mid-century modern manufacturers. Stag also played a big part in defining mid-century modern when they hired John & Sylvia Reid (again to compete with the Scandi influx) to design the S-Range, which came out to critical applause and are still seen as classics.

Nowadays British households are quite often a mash up of styles and designs. Even grand manor house country hotels will have the occasional mid-century modern sideboard or chair thrown into the mix to add modernity. Whatever furniture style you are drawn to or have a penchant for somewhere along the line Britain and its craftsmen and women have had some influence, be that the originator of that style or manipulating it to become more British.